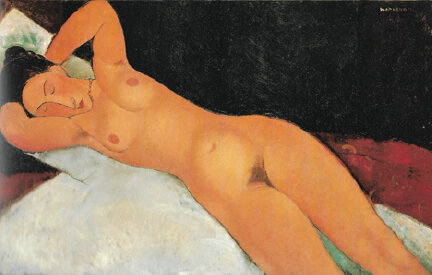

I was in high school when I first saw a Modigliani painting. I was much taken by the long sensual lines, the muted earthy colors, and the strange contradiction of an abstracted nude that yet, somehow oozed life and sexual allure. This vie comme (communication of life) is also in his portraits. Most of his paintings were nudes and portraits. Backgrounds were indifferently spare. He painted people. The individuality of the people painted ascends from the paint to confront you directly. This illusion animates what might otherwise seem only stylistic artifice.

He was not a realist painter.

He was a painter of reality.

This was a goal of every artist since Manet.

The universal use of photography made realistic painting unnecessary. Manet was one of the first to find a new role for painting – impressionistic revelation. From now on the point of panting would be to reveal what a photograph could not. Certain photographers will object, saying photos, too, can reveal more than reality. They are right to do so. Still, the rule holds.

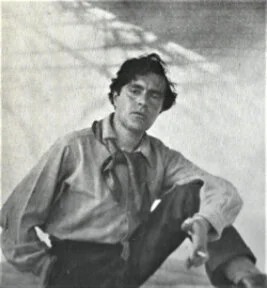

Modigliani flourished in the artistic hothouse of early twentieth century Paris. He mixed daily with the great painters and writers of the time, many of whom he painted. Most of them lived reckless lives, indifferent to practicality, and mad with Art. It was the perfect arena for youth, beauty, and talent. Modigliani had all three. He burned through his brief thirty-six years with all the romantic fervor you would expect from a Hollywood movie. His friend, Jacques Lipchintz, thought Modigliani accomplished all he wanted – “He said to me, time and again – une vie breve mais intense” He wanted the short but intense life he lived.

Modigliani / Reclining Nude with Necklace – 1917 / Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum / New York, NY

One model said he worked without stopping until he finished a painting. She could get up from the couch and walk behind him to see the progress; he barely noticed. I think he worked in something like a trance; conducting the paint toward some vision in his head that had nothing to do with technique or theory. That’s not unusual with artists. At the beginning of the Iliad, the poet Homer asks the Muse to sing, through him, the Wrath of Achilles. Opening yourself to a little help from above is always good.

Even when done without deliberate intent.

Modigliani’s paintings capture qualities of his subjects that probably neither he, nor any of his models, were conscious of. This absence of pre-conception may be why one of his friends said Modigliani’s paintings seemed to be created by the personalities of his subjects.

Drugs may have also played a role. The poets, artists, and writers of those days in Paris used many sorts, daily. Their pharmacy included: alcohol, ether, hashish, cocaine, laudanum, and opium. Most of these drugs have been around for centuries. Ether is an unusual choice as a drug. It can be deadly, and it is volatile. One young lady left her bottle of ether too near the stove. The explosion took out a wall of her apartment. By chance, she wasn’t home when it went off.

Many artists use drugs; only a few artists produce great art. The altered reality produced by drugs can sometimes reveal something to an artist that can be used creatively. The more common result is peripheral drama, and early exits – the effect on art is marginal.

Modigliani put away painting for a time to work at sculpture. The graceful elegance of his painting is little evident in his sculpture. His Muse was apparently uninterested in stone. Despite that, many art experts have reflected at length on fancied fine points in Modigliani’s abuse of innocent rocks. I cannot imagine why. Most of his “sculptures” could have been improved by being crushed into useful gravel.

I don’t think Modigliani’s failure at sculpture was due to lack of skill. I think the problem was that theory overwhelmed aesthetics. When Modigliani painted, he worked spontaneously, he allowed the subject and the moment to infuse his art. That can’t be done with sculpture.The sculptor, Brancusi, who lived nearby, may have influenced Modigliani with intellectualized notions of just how carving in stone should be done, with stylistic examples from Grecian caryatids, primeval symbolism, North African figurines – and much else that had nothing to do with life directly experienced.

It was the wrong medium for an artist that depended upon intimate contact with people. Fortunately, he returned to painting.

The people he painted flowed through him onto his canvases. Even when abstracted and stripped of background clues, each person he painted exudes personality. You may imagine you know them – or someone very like them.

Famous for his nudes, Modigliani painted many more portraits. Likely hundreds more. Many have been lost. So too, many of his drawings. His drawing style was fluid, impressionistic, and elegant. He captured expansive individualities with a few light strokes.

For many years, I saw his work only in art books. I didn’t know how little I knew until I stood inches away from a real painting. I was amazed at the compelling vitality – none of which comes across in reproduction. The painting was Portrait of a Women. I saw it at the Cleveland Museum of Art. There is something in the actuality that cannot be experienced with even the best facsimile. As I walked around the museum I realized the same was true of every work I previously thought I knew.

Modigliani has occupied some recess of my mind for most of my life. I’m not sure why. Youthful talent cut short is fascinating enough. But there is something more that would attract me even if I knew nothing of his romantically tragic life.

Something purely of his art.

Anna Zborowska, Paul Guillaume, Jeanne Hebuterne

He shapes everyone he paints into a personal iconic style. It’s beautiful, even when the subject isn’t. He does this without hiding the real person, but by transforming that person into a “Modigliani” person. Sometimes I wonder what certain faces would look like if they were painted by Modigliani. They would look familial, but differently distictive. They would become elegantly elongated, the turn of their head would become gracefully aristocratic, their innermost selves would seem secretly significant. Familiar eyes would become mysterious, both white of eye and pupil would disappear as the color of the iris would fill the entire eye. Unreal, yet more real. What conveys blue-eyedness more than a completely blue eye?

Reality magically become art.

That’s what charms me about Modigliani.

Modigliani lived his life as art.

Unfortunately, life will not bear art for very long. Modigliani played out his artful life with resolute romantism; oblivious to good sense, a threat to himself, and a problem for those who loved him. It couldn’t last. Shooting stars flame gloriously. Then they crash.

Absinthe, a type of greenish liquor favored by Modigliani, was rumored to have caused his death. It certainly could have. Absinthe is flavored with anise and wormwood.The anise is harmless. The wormwood is poisonous. He drank a lot of absenthe, but he died of tuberculosis, or some inflammation of the lungs that seemed like tuburculosis, possibly tubercular meningitis. His health had been deteriorating for most of the previous year. His fits of coughing now included coughing up blood. The cough kept him awake. Lack of sleep along with the chilly damp of an unheated apartment worsened whatever his illness was. He refused doctors; instead treating his disease with more drinking.

He was taken to hospital and died on the next day.

At the time of his death, he was living with Jeanne Hebuterne. She threw herself on his corpse, covering it with kisses. She had to be pulled away by the doctors who feared for her health, and the health of her unborn child.

Jeanne was unlike the many other women drawn to Modigliani. One commentator said, “He had all of Montmartre for his harem”. Another added, “If he didn’t sleep with every women he painted nude, he slept with most of them.”

Even so, he loved only one of them: Jeanne Hebuterne.

She was a good girl. She came from a good family.

Her good family disowned her for living with Modigliani.

It is not certain they were legally married, but Modigliani regularly referred to her as his wife, and she was mother of his only child, Jeanne Modigliani. He painted her more often than any other woman, all portraits, no nudes. Their brief love should be a story by itself, so unlike the rest of Modiglianl’s life. I would like to write about it, but I can’t. I have no details, only inference.

The day after Modigliani’s death Jeanne Hebutrane threw herself from the fifth-story window of her father’s house. She was nine months pregnant at the time.

“une vie breve mais intense”.

Amedeo Modigliani 1884 – 1924